I have been shocked at how many of my friends have called my

favorite movie of all time “incomprehensible” or “really weird.” Well, let’s get this part out of the way:

Yes, Spirited Away is my favorite movie.

The top of all my Top 100 Movies lists. In a range from 1 to 10, I give it an 11. I

honestly have a hard time imagining that another movie would ever beat it, but

it’s possible. And Hayao Miyazaki is my

favorite director. I have four of his

films in my top 100.

Now, back to my friends.

It stuns me how many people watch Spirited Away for the first time and

just don’t get it. It’s too confusing,

too gross, too weird. But I’ve never

felt that. Sure, there have always been

details I never got, but the heart of the film always made sense to me.

So I write this guide to assist those who don’t understand

the film. Partly because I want you to

love it as much as I, but mostly because I at least want the film to have a

chance. If it’s just one weird image

after another, that’s no fun. And

Spirited Away IS fun. I just watched it

again last night and I had a big silly grin on my face all throughout the

film. Okay, let’s try to stick to the

facts. I’ll try to calm my uber-geek

down.

What is this world?

So Chihiro (the girl) and her parents wander into an

abandoned theme park where there seem to be ghosts and weird creatures. And Chihiro runs into a large, beautiful

building, which we are told is a “bathhouse for the spirits”, but what does

that even mean? What is this place,

anyway?

This is where your Religion 101 comes in handy... What?

You never took a Religion 101? You

were drunk when you went to Sunday School? Okay, let’s start from the

beginning.

The basis of almost every religion is that there is an

alternative world that we will conveniently call “the spirit world.” It occupies the same space that we do, but we

cannot see it or feel it. Occasionally

the spirits of this alternative world (which we can call “ghosts” or “demons”

or “angels” depending on your spin) make small changes in our human world, but

mostly they leave our world alone. They

have their place, and we have ours. Oh,

and they can see our world, but we can’t see theirs. That sucks, huh?

Hayao Miyazaki’s universe (an alternative universe to our

own, which all his films are in) is deeply influenced by Shintoism, an

organized folk religion in Japan. In

fact, Miyazaki’s film My Neighbor Totoro is an excellent introduction to

Shintoism. Like many other religions,

every place, every body of water, every forest and desert has their own

spirit. Totoro is a forest spirit, and

the two girls are learning the way to respect and live comfortably with their

local spirits, which summarizes what Shintoism is about.

What happens to Chihiro and her parents is they wander into

a place where the spirit world and the human world intersect. You can read about these places in the Bible,

too—ever hear of Jacob’s Ladder? That’s

what happened to that lying thief when he stumbled across a cross point between

the spirit world and the human world.

Spirited Away is about Chihiro’s adventures in one of those crossover

places.

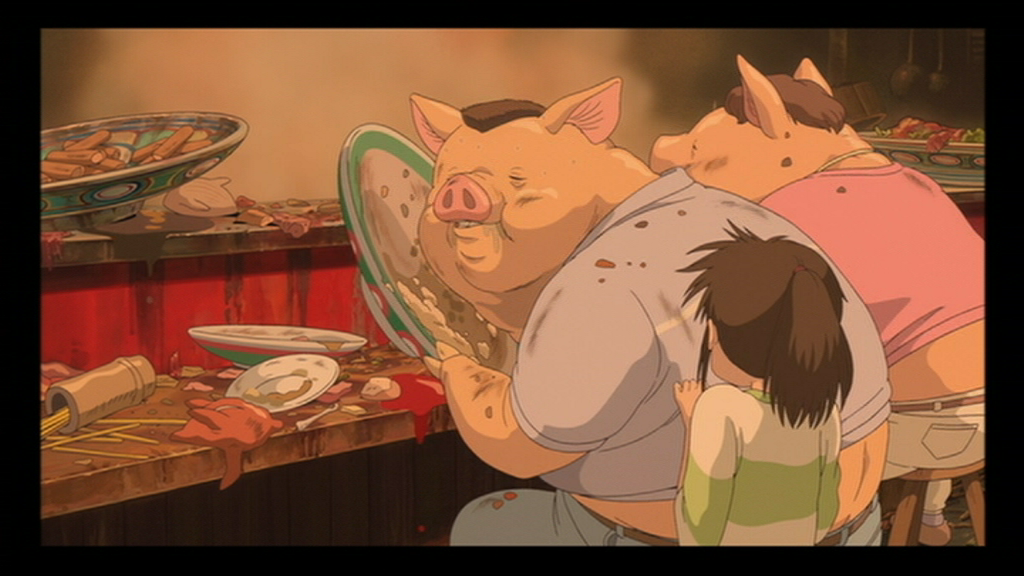

Why do Chihiro’s

parents turn into pigs?

When you have crossed over to the spirit world, one of two

things happen. The first is you

disappear. That’s because humans don’t

belong in the spirit world, so they wouldn’t exist there. Haku has Chihiro eat a bit of the spirit

world’s food, which gives her a place in the world.

Second, in the spirit world, you look like who you really

are. So the beautiful cheerleader who

teased you in high school? In the spirit

would she’d be as ugly as her inner person was.

Even so, Chihiro’s parents showed themselves to be gluttons, so they

turned into pigs. The fact that Chihiro

remained herself, shows how strong her character was.

Why does Haku help

Chihiro?

Haku from the very first is concerned about Chihiro and her

well-being. But why? As we find out more about him, we know that

he isn’t a tenderhearted guy. Everyone

talks about him as the kind of person who would see a baby on the ground, crocs

coming to eat him and he’d cross over on the other side of the road. And maybe kick the baby a little closer to

the crocs, just for fun. But he goes out

of his way, even to get himself in trouble, to help Chihiro.

And that’s because, we find out later in the film, Haku is a

slave to Yubaba. He’s stuck and he doesn’t

know who he is, or where he came from.

And his only clue is that he recognized Chihiro. You can see it as soon as he glances at

her. So Chihiro is his only way to

escape the slavery. Somehow, she is a

clue to his identity, which he can use to escape Yubaba’s clutches. So he has to care for her until he is able to

figure out how he can use her for his own escape plan.

So why is he so mean to her in the elevator? Because as long as he is in the bathhouse,

under Yubaba’s influence, he has to be 100 percent henchman. If she suspects that he has some connection

to Chihiro, his plan is lost. So this

means that all those girls fantasizing about a romantic relationship between

Haku and Chihiro… nope. He’s not

interested. Besides, he’s a spirit—they aren’t

even of the same species.

Why does Yubaba take

Chihiro’s name and give her the name Sen?

Yubaba is the spirit/witch who runs the bathhouse with

authority and a business-like charm. Her

character is based on the Slavic folk story Baba Yaga, who was an old witch who

lived in a house with chicken legs, who was sometimes mean and sometimes very

helpful. Possibly Yubaba’s sister Zeniba

is supposed to be the nice side of Yubaba?

She just gets cranky around thieves.

In the ancient world, to have another’s name is to have

power over them. So Yubaba has her

workers sign away their names, so that she might obtain power. Not just the power of them forgetting who they

are, but she can use the name to put curses or other magic on people through

the use of their name. It’s interesting

that Yubaba lifts most of Chihiro’s name off of the paper, leaving only the

word “Sen” (because the writing style they were using is pictorial, not

phonetic). This also means that

everyone’s real name in the bath house is different from what they are

called. And everyone in the bath house

is desperate for money—is this so they can buy back their names and escape

slavery?

What’s going on with

Stinky?

Yubaba claims that a stink spirit” is coming to the bath

house and everyone does their best to dissuade him away, but it’s no use. He comes in, smells up the place like a

porta-potty that no one has ever drained, and he takes his bath with Sen

helping. Sen then finds a “thorn”, which

Yubaba figures out, and after Lynn ties a rope onto the thorn, everyone in the

bath house has to pull it out, which is a bunch of garbage. Yubaba then declares that it is a river

spirit, and he provides everyone with wealth.

Okay, what?

So a river spirit would be a spirit that lives in a river,

but is also identified with the river.

So whatever happens to the river, happens to the spirit. The river was polluted severely to such a

degree that it smelled to high heaven.

He came to the bath house to get the human debris cleaned out of him.

The great thing is how everyone works together here. Sen had the compassion to see that something

was wrong. Yubaba had the experience and

smarts to put the pieces together. And

it took Lynn and the rest of the bath house to clean the river and send him on

his way. In this movie, the little girl

doesn’t do all the saving herself—she is simply the key through which saving

can be started. But it takes a community

to make peace. Or to clean up a stinky

river. Pretty clever parable, there,

huh?

What’s the deal with

No Face?

Although it’s kind of a side story, the plot surrounding No

Face takes up the center of the film and it is arguably some of the most

dramatic parts of the film. And it is a

key to the main theme of the movie.

Besides, much of what happens with No Face is simply gross, and why is

Miyazaki putting us through all that?

No Face first appears on the bridge as Chihiro is trying to

get across. He notices her immediately.

Later, Sen invites him into the bath house from a side window (oops,

broke a rule there). In response to her

kindness, he tries to help her out—stealing bath tokens, for example. He wanders about for a while, swallows a

talking frog, offers some gold and demands food. A lot of it.

All the food in the house, practically. All the while throwing gold

about for everyone to get rich, while he turns into a huge, hideous monster. Sen stumbles across him, and he offers her a

huge pile of gold, which she wasn’t interested in. Gold had nothing to do with helping Haku or

her parents, so she didn’t care. No Face

then goes in a rampage, swallowing other attendants and demanding Sen. Yubaba tries to help, but to no avail. Finally Sen comes in, tells him he has to

leave, and gives him a piece of medicine.

No Face starts vomiting all over the bath house, all the attendants and

froggy comes out fine, and then he throws himself in the river, where he

follows Sen to go to Zeniba’s house.

What is this insanity?

First, about No Face—he is a spirit without a center,

without a base character. He, like Haku,

notices her immediately, but not because he remembers her. He notices her because she has such a strong

center. Chihiro/Sen, from the time she

enters the spirit world is determined to save.

She needs to save her parents, and then she needs to save Haku, and

later she needs to save No Face. Her

center is her compassion or “love” for all of these people. It is her determination to love that is her

center throughout the film. No Face,

being an empty, lonely spirit, recognizes this immediately and is drawn to

her.

But once he gets in the bath house, he is turned away from

Sen by the powerful center of the bath house itself, which is greed. Everyone in the bath house is infected by

Yubaba’s greed. Some have the greed for

gold that she does, but others have a greed for freedom, a greed for food

(mmmm, roasted newt!), a greed for whatever they don’t have. Caught up by this gluttony and avarice, he

(literally) ingests it, and demands more and more, using his magic to make dirt

look like gold, and an orgy of greed ensues.

But what No Face really wants is a true friend, someone who

really cares about him. So when Sen

refuses his trade of gold-for-relationship (if only he had listened to the

Beatles!), No Face is confused and goes on a rampage. Realizing that Sen is the only one in the

bathhouse that will give him the love he needs, he demands her like a crying

toddler after his mommy. Sen finally

meets with him and realizes that he is sick, just as sick that Haku was with

the paper wounds. So she offers him the

medicine, and he begins vomiting out the illness—the greed. Only after the greed was completely expelled

was he empty enough to accept the subtle but caring touches Sen offered him.

This greed v. love theme is the center of the film. Haku got trapped in a cycle of greed when he

came to the bathhouse, coming to steal magic and becoming a slave to Yubaba’s

greed instead. But he is set free from

her curse by Sen’s love and compassion for him.

The parents are trapped because of their gluttony to eat that which did

not belong to them, assuming that their money would buy anything. Sen’s love and determination frees them.

Greed is a slavery

that love delivers us from. Do you hear

that, capitalist pigs?

What is Spirited Away

about, anyway?

Ultimately, Spirited Away is a coming of age movie, not too

unlike Miyazaki’s film Kiki’s Delivery Service.

Like that movie, Spirited Away shows a girl who’s determination and hard

work causes her to mature.

But Spirited Away goes further. At the beginning Chihiro was a normal

pre-teen girl—grumpy, anxious, full of irrational complaints (apologies to my pre-teen daughter). The only thing that saved her in the movie

was her determination to save others.

Only when she realized that her parents, Haku, No Face and others

depended on her to deliver them, did she have the power to grow up. Hard work is a factor, like all Miyazaki

movies, but the hard work that makes changes in the world is the effort of

compassion. That’s what makes the world better.

That’s what makes US better people.

Some people are lazy gluttons (the parents), and some people are hard

working for their gold (bathhouse attendants), but to grow up, we have to

determine to work for others.

I love this movie because I love watching the imagination

just go crazy. I love watching the

fanciful characters, and the adorable characters like the soot creatures,

Kamaji the boilerman, and the Radish Spirit.

Yes, the Radish Spirit. Love that

guy.

But mostly I love

this movie because I get to see Chihiro grow up. She becomes a confident young woman, ready to

face the world. No longer naïve, but

really understanding the power of compassion and how it changes people. So awesome.