I found that the danger of watching the Lobster is laughing

too hard at it. Unless I am willing to

laugh equally hard at myself.

The director/writer of a trilogy of film said of his first

two films that Dogtooth was about a created fiction to protect their children

from reality. That Alps was about a

self-imposed fiction in order to protect oneself from grief, for our own good.

In taking that idea to the next stage, what if all of

society was a fabrication? What if we

needed to hide reality from our own eyes in order to keep us all conformed to

an artificial structure?

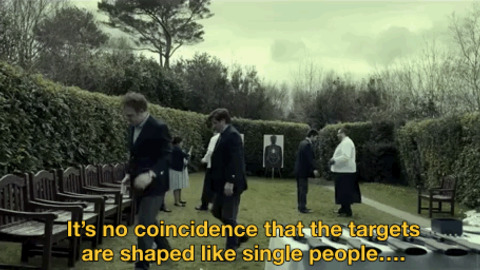

It might be easy to look at The Lobster and see it as a

ridiculous comedy, full of insane situations.

But we see situations like these daily.

Do we not feel the threat of sexual nonconformity, the ostracism, even

physical threat? Are not many willing to

accept idiocy and clear fiction for the sake of conformity?

Are many not willing to go through gross and disgusting

physical deformities (which might be called “augmentation” in order to maintain the façade of love that

has nothing to do with those deformities?

Does not our society create a series of verbal and physical

facades in order to perpetuate a false pretense of romance and marital

bliss? Of course society’s restrictions

are not just about sexual mores but also class and culture and security and on

and on. When we look at society’s

fictions they pile ever higher.

Our fictions go ever deeper.

As if presidential elections change anything, as if our jobs our

meaningful, as if our enemies were really enemies and no fellow human beings,

as if making changes in our lives do anything else but establish our placement

in a different level of the self-appointed façade.

The Lobster invites us to laugh at ourselves. To see the facades for what they really are. And

also to see the dangers of the fictions we blindly accept.

I am tempted to ask the question, "Was it

good?". But I'm not sure a vision

of a subversive, existential prophetic vision should be limited to such words

as "good" or "entertaining." That kind of misses the point, doesn't it?