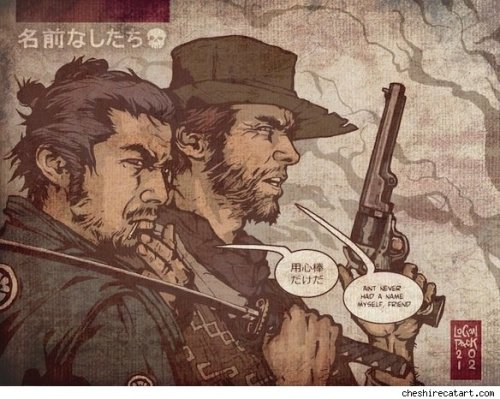

Part I: Mor'du

I was not always as you see me now.

I was once a powerful man, a ruler of men, a commander of armies. While my father was the High King, I ruled under him, taking charge of his armies, conquering peoples and making his empire strong. When my dear father gave me my charge to conquer, he handed me my most precious possession: the Ring of the Double Axe. It was too dear to me to place on my finger, so I wore it on a metal chain around my neck, so it might never be removed. Then I set my face to gather land for my father. And so I did.

My three brothers were nothing and did nothing. Mortek, the oldest, spent his days travelling from one pub to another, drinking his fill with masses of peasants and merchants. Morbus lived in libraries, always putting his nose in a book. Moder, the youngest, spent his days in the forest, where his companions were rabbits and squirrels. What did they know about ruling an empire? They had no real experience.

Yet when my father died, they all stood to take charge of the empire. Morbus presented a proposal that we should rule the land together, but I refused. I was the only one who understood warcraft, the handling of men, the manipulation of real power. How could I share such power with the weaklings my father produced?

But they dared to stand against me. Morbus had a number of the army on his side. And though his forces were small, they were smart and underhanded and diminished my forces. Moder called up the animals of the forest, and his army of bears and antlered deer slashed the leather armor off of my men, damaging them. Mortek rose up an army of peasants, and his merchants paid for armor and swords. They were inexperienced, but they had passion.

In my rage, I rose up personally against my brothers, but I knew that I could not reach them, surrounded as they were by soldiers and bodyguards. So I went to the Witch of the Woods and demanded that she give me the strength of ten men. She warned me, however, that the spell would only cease if "that which is broken be mended". What would that matter to me? My strength is what was significant.

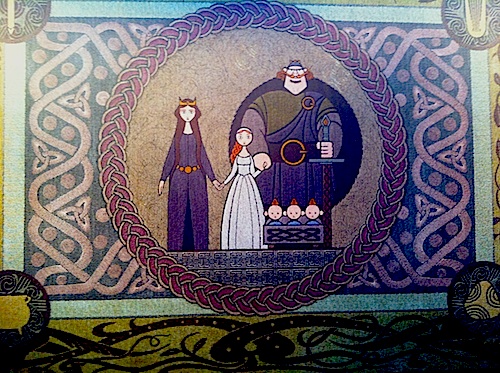

So I called my brothers to a meeting under a flag of truce. They gathered, with their men-at-arms in the cave where our father had placed the treaty stone, with the image of all four of us standing together. When they arrived, I took the potion, and they watched as the transformation took place.

It was not as I expected. I did not turn into a Hercules, a god. I turned into a bear. And my blind rage took over my powerful paws.

I broke the stone of treaty, and reached out and killed my three brothers. The rage dissipated, and I was left with brokenness and blood. Only then did I realize that I needed Morbus' knowlege, Moder's natural powers and Mortek's community connection. Only then did I see my folly. And I could not mend what was broken. I had broken too much.

After a day my rage returned. I have lived by instinct ever since.

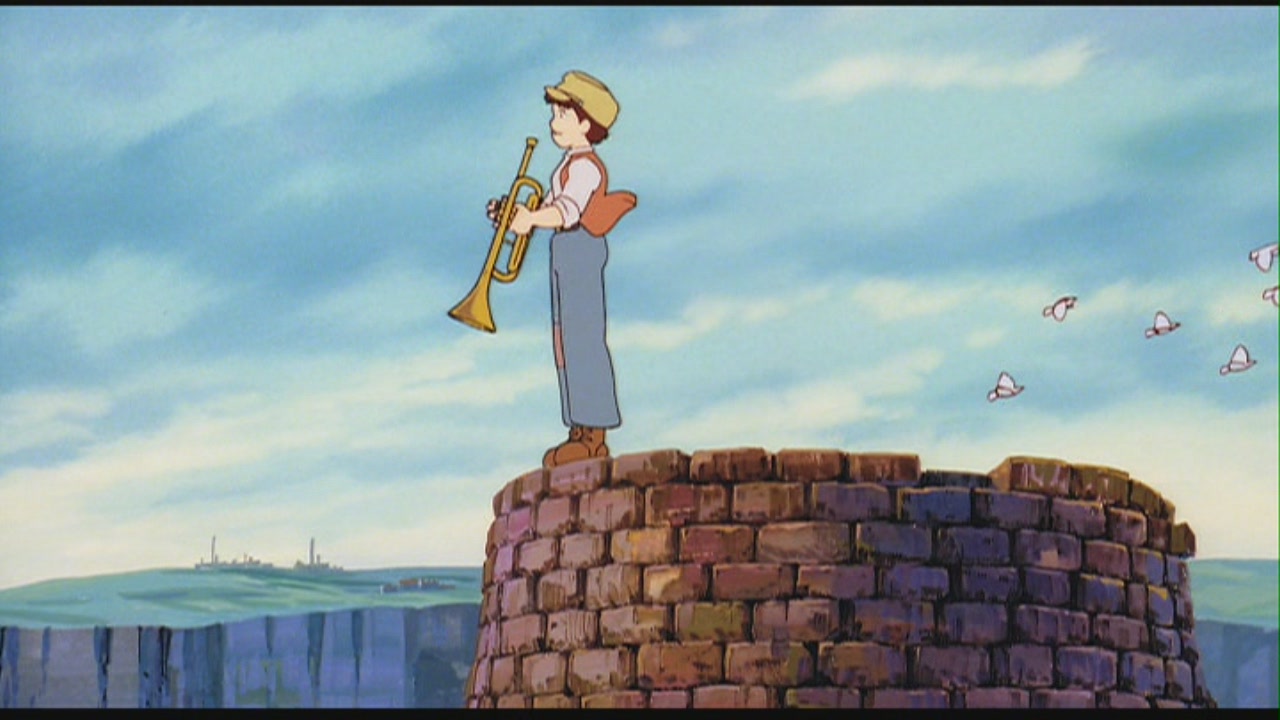

Part II: Tiers of Pixar

Pixar has a few tiers of film. There is the entertaining

film: Cars 2, A Bug's Life, Monster's Inc.. There are the films that are so

stunning that it is hard to speak after the first watch: Wall-E, Up,

Ratatouille. Then there are the films that grow on you.

Perhaps I didn't think much of the film first time I saw it.

It's okay, pretty, fun. But nothing deep. Then your kids watch it again, and

you happen to be in the room. Hum. And again, but this time you sit down and

watch it with them. Soon, you find deep lessons for your life in the film, and

as simple as it seemed the first time, it is more enriching the more you watch

it.

That's Finding Nemo. And Brave.

Just watched it again yesterday and as much as I enjoyed it

in the theatre, it didn't make me cry like yesterday. This second full viewing

really spoke to me and a lesson for all of us. Relationships are more important

than our pride. That's what makes us have satisfying lives.

The animation is so excellent in this film as well. No, this

film doesn't stun me. And it doesn't speak deeply to my heart. But it is that

most precious of all films for me. It grows.

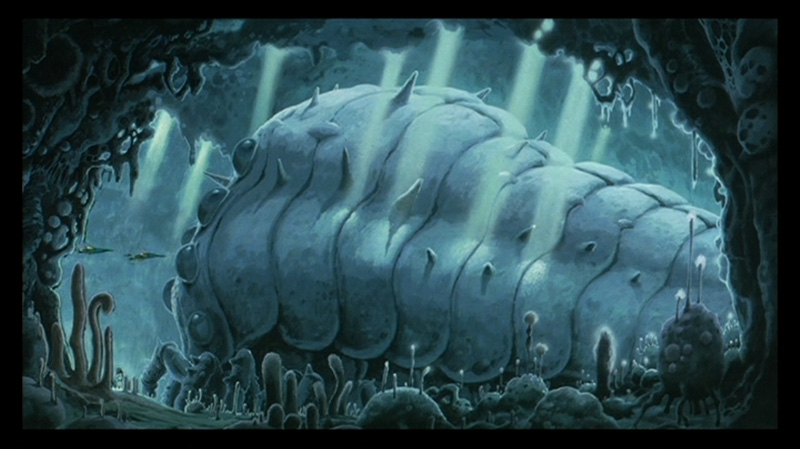

Part III: What is the Message of Brave?

***Warning! Major spoilers below!!!***

The main story of Brave is easy to see: a mother/daughter tale, where they needed to understand each other better, and only when the mother is transformed into a bear could this occur. The story might seem too similar to another Disney film, Brother Bear, but Brave makes more sense, is funnier and has more sympathetic characters.

The key to the film, however, is to determine what breaks the spell. What is "the bond torn by pride" that must be mended? Merida thought that it was the tapestry, and many viewers thought the same. However, just because the tapestry was mended, it didn't break the spell. Part of the tension of the film has to do with Mor'du's spell, which is broken at his death (after which he turns into a will o' the wisp), but even then Merida's spell isn't broken.

Certainly the "bond" has to do with the relationship between Merida and Elinor. But we see them getting along quite fine in the forest, and Elinor already signaled Merida to declare a compromise that both could approve of. So their conflict is finished, right? Yet the spell is not broken.

The "bond torn by pride" is their relationship, but it was broken by both sides. Elinor agreed that she had gone too far, and delayed a betrothal (Although it must be noted that a betrothal was not set aside. The original contract between the four peoples was that a marriage would occur between Merida and one of the three boys. That still held, they just gave the young people time to make their own decision as to which one it would be.) How did Merida break the bond? What did she need to do to mend it?

The key is in Merida's many declarations of innocence after he mother turns into a bear. She is constantly deflecting blame for her actions. She blames Elinor, blames the witch for giving the "wrong" spell. But it isn't until the final moment that she admits her own responsibility for harming her mother.

That act of repentance at the climax of the film is what breaks me. It is the sorrow of the prodigal, the shame of the morally weak, the breaking of the pride that tears. And in the end, that is what is complex and beautiful story is about. To truly mend the tears between relationships, we must admit our own actions. We must have sorrow for our own wrongs done.

The relationship was torn by two parties, as is most of the time the case. And there cannot be true restoration until both parties confess their actions in causing the rift.