There are no spoilers in this analysis of an aspect of

Ratatouille, but I’m assuming if you're interested in reading this, you’ve seen

the film.

Ratatouille isn’t standard children’s fare, but it is a

child’s fantasy: suppose a rat was a foodie, a natural chef, and suppose he

could control a human well enough without speech to cook food on the very

highest level. Not very believable, but

fine for a kid’s film. Then, the final

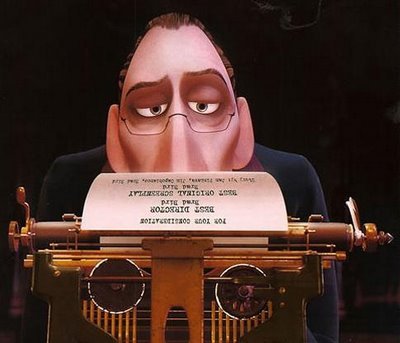

test comes, Anton Ego, the most pompous critic in town, arrives to review this restaurant

he’s heard so much about.

Until this point, Ego is a stereotype, the shell of a human

being, the negative critic who could be expected to sniff at the food. Of course, Ego could be expected to exclaim

his loud praise and run into the streets demanding people come in to eat this

food. That would suit the character of

the film, but not the film's character.

At this moment Ego is fleshed out and we see who he really is: a

particular man, an introvert who has high expectations, but when those

expectations are met or exceeded, then he does not yell, but his emotion is

just intense.

And just as personal.

His response is not only about food, but about his childhood

experiences. He knows that his reaction

is subjective, but he can't help it. He

has experienced art in the deepest, most intimate level, and this experience

changes his life. This is really about

the response every artist dreams about-- the inner touch that only that one

lover, the loving mother, the life-long friend can have. An artist only has a moment, perhaps a matter

of hours, to touch a human being so deeply that they will never forget it, and

it changes how they see the world around them.

Suddenly, the world is brighter, clearer, closer. This is the true moment of every artist who

has ever lived.

Ego is suddenly packed with humanity and life. It isn't enough to say that Bird gives

critics a good shot while others' dismiss critics. Some films skewer critics, while others

literally have them killed (in the film, of course). Bird makes his critic not only his eloquent

spokesperson, but a genius who perfectly combines opinion and word to elevate

everyone's perception of a particular piece of art. Ego is the personification of the power of

criticism, an artist in his own right.

Some claim that critics are leeches, at times borrowing, at times

darkening the shining glory that is art.

But in Brad Bird's world, the critic is the artist who can empower art

to be art, or to dissolve the work of the faux artist. Perhaps Bird has such a good opinion of

critics because even when his work was less than very successful (Iron Giant),

the critics sang his praises, saw his art for what it really was.

Bird gives the power to critics that they sometimes

deserve. And in turning shallow

creatures (Linguini, Ego, and to a lesser extent, Colette) into full characters

in the final act, he also enriches the film to be a fuller film. It is no longer about childish fantasy, but

about a unique perspective on adult realities.

Pixar magic, when they take the time to use it, is not just about excellent storytelling, but also about taking the time to make characters more than a millimeter deep. Ego could have been just a throwaway one-note character, but instead they take the time to give us a background and a more complex motivation.

They do this a lot with supporting characters-- Jesse the cowgirl in Toy Story 2, Doc Hudson in Cars, Mirage in The Incredibles, Gil in Finding Nemo. How many animated films take the take to make real people out of side characters. But it is this that makes many Pixar films full worlds and not just fluff.

No comments:

Post a Comment