The Hours is a film of three stories about three women all living a form of the life of Mrs. Dalloway, the lauded novel by Virginia Woolf. The first story is that of the author herself played by a gaunt, frail Nichole Kidman. She uses the novel to struggle with her inner demons, to which she eventually subcumbs (as we see in the first scene of the film).

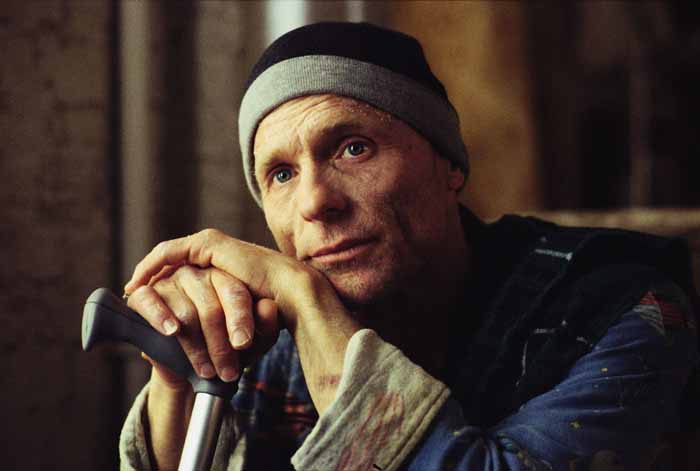

Then there is Mrs. Brown, a housewife in the 50s, masterfully played by Julianne Moore. She has the perfect life, the perfect husband, the perfect, beautiful son, yet she is inadequate for this very life she is living. The third woman is Clarissa, played by Meryl Streep, a book editor who struggles to keep her dear friend, poet and ex-lover involved as he struggles with AIDS.

The brilliance of this film is the weaving of these three stories into one coherent whole about life and happiness and relationship. This is cinematic literature, depth in film at its finest, even if it wears its literariness on its sleeve. The film is held strong by its amazing cast, including John C Riley and Ed Harris, who take the great ideas and encapsulates them into a reality that touches us and breathes. Even the editing is top-notch, clearly spelling out a narrative that could easily be confusing for frustrating, but never is.

One of the greatest aspects of the film are the touchstones of themes in the story. There is a desperate kiss in each story, each protagonist collects flowers to maintain a semblance of normalcy, and they all have an individual that keeps them alive and breathing, often out of duty. The deeper we look into this film, the richer we find it.

* * *

Is the purpose of life happiness?

Happiness is so fleeting and life continues long after happiness has passed. A life might be spent pursuing happiness, but that goal might be too lofty to be achieved, yet does that make the life any less meaningful? Certainly life must have a certain level of contentment, a low level of happiness, a sense that "yes, this is the direction things should be going in." We must have a satisfaction with who we are, what we do, lest we perpetually be in transition. At the very least, we must hope that who we are will eventually be enough to satisfy ourselves.

But what if we have obtained happiness, all the things that we have reached for we finally achieve, all the hope realized and then, mysteriously, we are still not content? Some might say we are ungrateful, but the inner emptiness has noting to do with appreciation. We can be amazed and thankful of how far we have come, but it simply isn't enough. Perhaps the goals we achieved were wrong headed to begin with, or perhaps our emptiness will never be filled. We don't know. And the ache becomes more and more unbearable.

To obtain contentment, we must have peace both in our environment and in our hearts. To claim that one or the other kind of peace is all that is necessary leads to despair, causing one to fall in the personal void of discontent.

Struggling with this void comes naturally to those who have no control over their own life decisions. Their lives are taken out of their hands and their happiness and contentment is determined by those who only see a shadow of their deeper selves. There may be fleeting glimpses of bliss, or the opportunity to build the life of another, but this is inadequate to avoid despair over the long haul. When we have no say in our own lives, the natural result of this is discontentment. The vulnerable life is the despairing one.

Perhaps contentment is essential, but if we see the basis of life as our own personal happiness, that would deepen the discontentment, because it can never be ultimately achieved. But what else is there? Compassion? Building society through family or other means? This is the core of our being, and we must discover it for ourselves. In the end, the determination of what gives our life purpose is a solitary determination.

Then there is Mrs. Brown, a housewife in the 50s, masterfully played by Julianne Moore. She has the perfect life, the perfect husband, the perfect, beautiful son, yet she is inadequate for this very life she is living. The third woman is Clarissa, played by Meryl Streep, a book editor who struggles to keep her dear friend, poet and ex-lover involved as he struggles with AIDS.

The brilliance of this film is the weaving of these three stories into one coherent whole about life and happiness and relationship. This is cinematic literature, depth in film at its finest, even if it wears its literariness on its sleeve. The film is held strong by its amazing cast, including John C Riley and Ed Harris, who take the great ideas and encapsulates them into a reality that touches us and breathes. Even the editing is top-notch, clearly spelling out a narrative that could easily be confusing for frustrating, but never is.

One of the greatest aspects of the film are the touchstones of themes in the story. There is a desperate kiss in each story, each protagonist collects flowers to maintain a semblance of normalcy, and they all have an individual that keeps them alive and breathing, often out of duty. The deeper we look into this film, the richer we find it.

* * *

Is the purpose of life happiness?

Happiness is so fleeting and life continues long after happiness has passed. A life might be spent pursuing happiness, but that goal might be too lofty to be achieved, yet does that make the life any less meaningful? Certainly life must have a certain level of contentment, a low level of happiness, a sense that "yes, this is the direction things should be going in." We must have a satisfaction with who we are, what we do, lest we perpetually be in transition. At the very least, we must hope that who we are will eventually be enough to satisfy ourselves.

But what if we have obtained happiness, all the things that we have reached for we finally achieve, all the hope realized and then, mysteriously, we are still not content? Some might say we are ungrateful, but the inner emptiness has noting to do with appreciation. We can be amazed and thankful of how far we have come, but it simply isn't enough. Perhaps the goals we achieved were wrong headed to begin with, or perhaps our emptiness will never be filled. We don't know. And the ache becomes more and more unbearable.

To obtain contentment, we must have peace both in our environment and in our hearts. To claim that one or the other kind of peace is all that is necessary leads to despair, causing one to fall in the personal void of discontent.

Struggling with this void comes naturally to those who have no control over their own life decisions. Their lives are taken out of their hands and their happiness and contentment is determined by those who only see a shadow of their deeper selves. There may be fleeting glimpses of bliss, or the opportunity to build the life of another, but this is inadequate to avoid despair over the long haul. When we have no say in our own lives, the natural result of this is discontentment. The vulnerable life is the despairing one.

Perhaps contentment is essential, but if we see the basis of life as our own personal happiness, that would deepen the discontentment, because it can never be ultimately achieved. But what else is there? Compassion? Building society through family or other means? This is the core of our being, and we must discover it for ourselves. In the end, the determination of what gives our life purpose is a solitary determination.

No comments:

Post a Comment