|

| Scar, the brutal Comanche warrior |

Amidst my friends on the Filmspotting Forum, there has in

the past been a debate as to whether the classic John Ford Western is

racist.

It’s a very good western.

Most of the performances are weak, but the direction and storytelling

are powerful. The buildup to the first

Comanche attack is a perfect example: The audience knows what will happen, but

the family in the farmhouse doesn’t, but they gradually gain more signs and it

builds until the oldest daughter screams.

What a perfectly done scene.

| Our heroes? |

The story is pretty basic: John Wayne and his companion Jeffery Hunter

seek out a kidnapped girl and perseveres until they find her. It is the many details that make this

film. The hints of an old crush a woman

has on her husband’s brother. The casual

avoidance of telling any details because of the horror seen there. The occasional perspective of a woman waiting

for her noble, tongue-tied paramour. A

couple characters that are Swedish immigrants.

Just as interesting is what the film doesn’t tell us. We never find out what happened to Ethan in

the three years between the Civil War and the beginning of the film, even when

certain things are begging to be explained.

Nor do we find out what happens to Ethan after the film, although he was

going to be taken to trial for murder. Each

detail means nothing in itself, but put together, this film is a whole world, a complex of

activity and life.

But is it racist?

There is no question that John Wayne is racist. Not the actor, but his character in the

film, Ethan. A point is made of it in

the film. There is one group of Native

Americans, the Comanches, whom Ethan completely despises. He will kill them if he has a chance, his

companion, Martin, is concerned about what he would do when he meets the

Comanches and when another main character identifies with this group, he

attempts to kill that person as well.

However, just because a character in a film is racist doesn’t

make the film racist. Martin, a

fifth-blood Cherokee isn’t racist at all, and sees Ethan’s racism as a danger

in their overall goal: to rescue the girls of a destroyed farm family. Certainly in other films, pro racist

statements are make more boldly, such as American History X or Do the Right

Thing, yet the films are clearly anti-racist.

Just because a main character is racist doesn’t make the film so.

| Ward Bond and John Wayne |

The confusion comes in because

of the strength of Wayne’s character.

John Wayne, as usual, is the strongest presence in the film, with only

occasional scene stealing from Ward Bond, playing the Reverend Captain Samuel

Johnson Clayton. But, oddly enough, he is also often the wise

and even the ethical voice of the film.

Ethan shows knowledge beyond what one might expect, including multiple

languages. He knows the habits and

customs of many different cultures. He

knows when to allow the horses to rest and when an informer is really a

betrayer. Everyone else in the film is

slow or simply average. Ethan alone

shines.

Perhaps Martin is the

ethical voice. He stops Ethan from

killing and expresses more liberal values.

But if he is the ethical voice, it is a weak voice. He is committed to doing right, but at the

cost of his girl and the life they should be having together. He returns home to disrupt her wedding to

another man, and then he leaves again.

This seems like a strange action for a moral model.

|

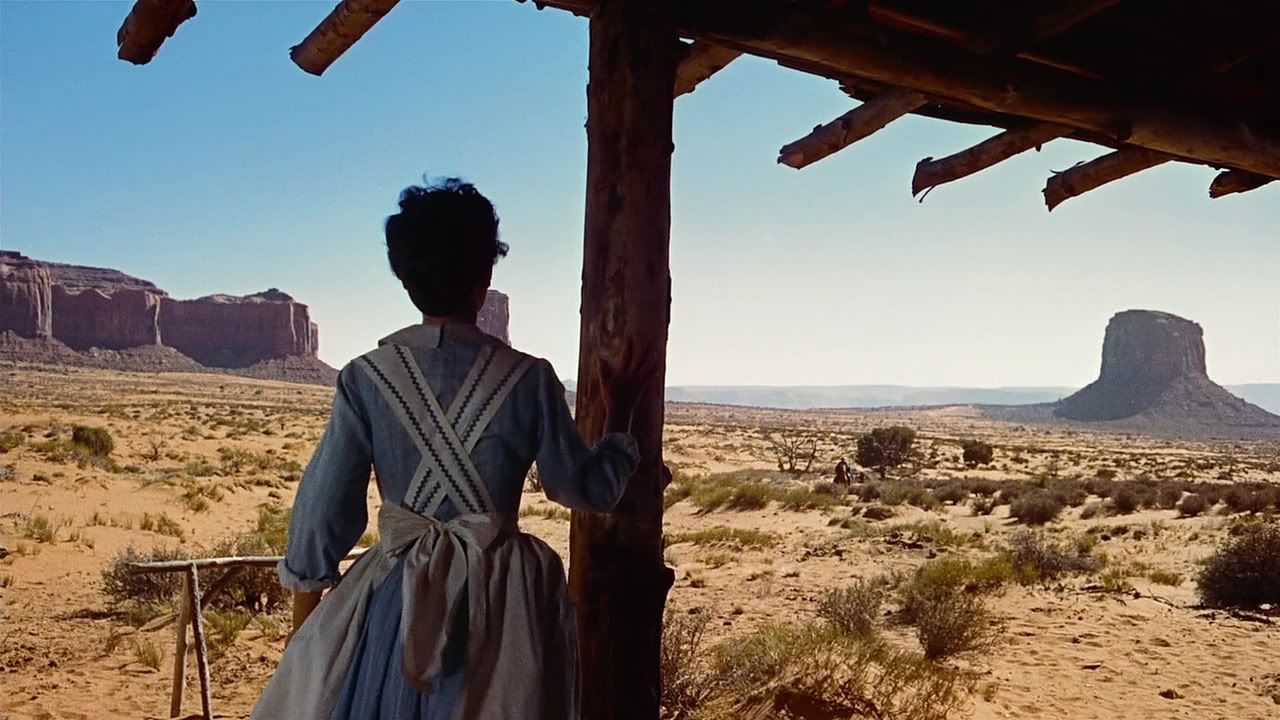

| Monument Valley is the beautiful backdrop of the film |

In the midst of a confusing

mix of details, we could get bogged down for a long time. Perhaps it would be better to focus on the

main moral theme of the film, and see if we can make any headway there.

There is one strong

recurring theme in the film, and that is family. Martin constantly chaffs at the fact that

Ethan doesn’t consider him family.

Martin was found by Ethan as a baby, and was raised by Ethan’s

brother. Yet Ethan makes a clear

distinction between blood family and others.

There is a responsibility, an eternal loyalty to blood family, but

others can come or go—it doesn’t matter.

Family was attacked, family

values attacked and family loyalty is tested over a period of years.

For Ethan, this loyalty to

family extends to peoples. Ethan has a

great respect for almost all peoples.

They have their own values and culture and Ethan gives them enough respect

to learn their languages and ways, so he can best communicate with them. But when a member of his family verbalizes a

rejection of their people, the Ethan must kill that traitor. There are clear lines between peoples, and

these lines must not be crossed, which is probably the reason Ethan has a hard

time accepting Martin. Ethan’s

philosophy is a consistent one, and one’s loyalty to family is strongly

connected to race, and thus to racism.

Martin, of course, voices a

different way of looking at things. He

is mixed race himself, and believes that one’s family has more to do with love

and connection rather than blood. He

searches with Ethan in order to protect the world from Ethan’s prejudices. In this way, Martin is the most redemptive

person in the film, the one with the noblest quest. Nevertheless, the film is not really about

his quest.

|

| Natalie Wood as Debbie |

In the end, which point of

view wins? The only way to determine

this is to discuss the ending of the film, so if you want to avoid spoilers,

please stop reading now.

Debbie, the kidnapped girl, is found by Ethan and Martin after years of searching. When found, she meets them and tells them to go. She has married a Comanche warlord and they are now her people. This is when Ethan tries to kill her, but Martin stops him. When the Comanches follow the duo, they find Debbie again, and after her husband is killed, she gleefully returns back to the European world, making it clear that she never wanted to be with the Indians at all.

Debbie, the kidnapped girl, is found by Ethan and Martin after years of searching. When found, she meets them and tells them to go. She has married a Comanche warlord and they are now her people. This is when Ethan tries to kill her, but Martin stops him. When the Comanches follow the duo, they find Debbie again, and after her husband is killed, she gleefully returns back to the European world, making it clear that she never wanted to be with the Indians at all.

I believe that Debbie’s

decision indicates the leaning of the film.

She, too, holds to the same values as Ethan. She is loyal to her family, and only rejected

them to save their lives. Her real

people are the people of her blood, not the people she had lived with for so

many years. And the final scene, that of

Ethan carrying Debbie away, is the glorious and right conclusion. Blood is thicker than experience.

I will not go so far to say

that The Searchers is a racist film. It

is not preaching racism, and it does have Martin as a counterpoint to Ethan’s

extremes. But it is a movie about

blood. How important it is to be loyal

to blood. How blood is more important

than anything else. This is not racism,

but it is it’s cousin. Because to demand

loyalty to blood before all else is to make other relations secondary. So the brother who is in need of a new car is

a greater requirement to meet than the homeless man who needs a meal. And the cheap oil one needs to give one’s

family a better lifestyle is more important than the hundreds of thousands of

non-Anglos killed for the sake of that cheap oil.

In the end, Ethan’s fate is

left open. So is the fate of his

philosophy. The film leans toward Ethan’s

ideals. As do most conservative

philosophies and religions. But it is still possible that Ethan will be hanged

for his murder.