There is more to Frankenstein than meets the eye.

Originally written as a philosophical horror

novel by Mary Shelley—a stunt to impress her friends—it has become a fable, a

warning. The novel spoke of what it

takes to be human, and how a thing created by humanity could or could not be

counted as human. The James Whale/Boris

Karloff film stated their theme right at the beginning of the film: There are

some pursuits that man should never explore, for they remain only in the hand

of God. In a sense, these represent the

two most popular themes in which the fiction enters into culture: The

recognition of sentience, even if made by human hands; and, the limitations of

science. This has clearly entered into

our current discussions on cloning, but also on artificial intelligence,

genetics and potential contact with extraterrestrial life. The ethics of these discussions can be linked

to the ethical discussions of either the novel or the film Frankenstein.

This influence is not strictly limited to the English

speaking lands, either. Mocked though it

is in some circles, Pokemon: The First Movie owes much to the novel

Frankenstein. MewTwo is a cloning

experiment gone array, with great

powers, but out of the control of his creator.

MewTwo determines to use his

powers to attack all humanity for their indifference and abuse of his species,

Pokemon. In the end (this is a spoiler,

in case you were dying to see this film), he realizes that humanity does have

compassion and love for Pokemon and calls off his attack. Like the monster in the novel, Frankenstein,

MewTwo is allowed long, rambling soliloquies.

It is frankly a better and more ethical film than most people give it a

chance to be.

The Spanish film, The Spirit of the Beehive, directed by

Victor Erice, wears its influence on its

sleeve. The movie opens with a scene

showing the town where the action takes place watching the Whale film

Frankenstein. Erice himself said that

the whole film is encapsulated in one scene from that original film, where the

monster is throwing flowers in the lake with a little girl. We can see this influence throughout the

film, as different characters are seen to be like the monster or similar to the

doctor of the Whale film. The monster

from the Whale film even makes an appearance near the end of Spirit.

But what Spirit of the Beehive is actually about is

difficult to determine. Clearly it is

rich with symbolism. Symbols of death

abound. Characters wander or pace

without much purpose. There is a rich

background, but no explanation given as to the import of the background. The movie focuses on the little girl, Ana—played

marvelously by Ana Torrent—but is the film about her, about her family or about

the town? Or is it about all of us?

A little bit of study (and watching a documentary on the

film supplied by Criterion Collection on their DVD package—thanks again,

Criterion!), gives us a better understanding of the film. I won’t give away any spoilers, here, but I

think there is some information that is helpful to understand. The Spirit of the Beehive was made in 1973,

near the end of Franco’s regime in Spain.

The film takes place in 1940, when Franco’s takeover just occurred. Ana’s family was involved with the leftists,

who opposed Franco. Ana assists a rebel

against Franco’s regime. The

listlessness of the parents are due to the fact that they have nothing to work

for, as they have no place in the new regime.

Thus, The Spirit of the Beehive is one of the great pieces

of art to come from protest of Franco’s actions. This list includes Hemingway novels, Dali

paintings, and, in this millennium, films by Del Toro. Erice remains symbolic and indirect because

he is making this film under Franco’s rule, in Spain. Like the Russian filmmaker, Andrei Tarkovsky

, the censorship he must work under causes him to create works of art that are

brilliant and intellectually statisfying the more one watches them. However, unlike Tarkovsky , Erice has created a work of such deep

humanity and joy alongside the hidden meanings and despair, that it is a

pleasure to watch. While Tarkovsky is

often a towering intellect, The Spirit of the Beehive is not only

intellectually satisfying, but is also wonderful film about childhood and the

joys and confusion that we all have when children. It communicates the isolation we can often

feel from those we should be closest to. It connects to all of us.

Finally, what does the Spanish Civil War have to do with

Frankenstein? How could Erice and Angel

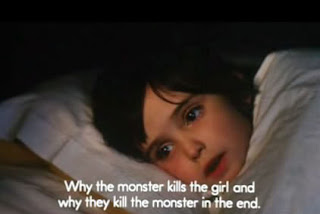

Santos—the writers of the film—have conceived such a connection? It is found in the answer to Ana’s question

after watching the film Frankenstein: “Why did the monster kill the girl? Why did they kill him?” The answer is given in the film: When you are

separated from your humanity, then the most inhuman acts are accepted. The Spirit of the Beehive is filled with people

who see themselves as separated from humanity as the monster was in the

film. And there have been many regimes

that have caused such destruction of people’s souls, thus resulting in the

destruction of many bodies. This film is

a protest, not just against Franco, but against any government that limits the

humanity of its own citizens.